Portraits of Ethnography

Doing ethnography via public art, we witness its power to push public consumption, overturn stereotypes, and provide a unique type of theoretical backing to human narratives and historical events.

Angie sat very still, her hands folded neatly over her lap, her head high, looking beyond the cramped quarters of the shelter; beyond the crowd that had gathered around her, the children peering around adult legs and making faces that made her laugh; beyond Meghan who darted behind the canvas looking far more intense than her usual jovial self, even with the red and green paint splashed on her clothes and her face. Angie sat on the couch for over two hours and even after the crowd had dissipated, bored of her stillness, she continued to look beyond the artist’s frantic activity. One could see that while her gaze was forward looking, her mind was elsewhere – in fact as she later told me, lost in the past.

“I sat there for so long,” she told me afterwards, looking at her finished portrait, “that I got to thinking about many things. I was thinking for a long time about my dad, who doesn’t know I’m pregnant and about my mom who was angry I left. I thought a lot of when I met Fernando, and how happy I was when I found out I was having a girl. I thought of how they came to tell us that we had to leave, that they wanted to kill us because Fernando had a fight with a man who was a paramilitary. I was looking at everyone looking at me and I remembered how sad I was here when we first arrived at the shelter and then how last week that man called me dirty ‘negra’ in the street. And now this painting is here and I’m proud because it’s going to go far away and people will see me all over the world.”

In 2013, Brooklyn-based artist Meghan Keane came to visit me in Soacha, a Colombian city south of Bogotá where I had been doing fieldwork for almost a year. Together, we visited the New Horizons Foundation, a central locus of my anthropological research. The country’s fifty years of civil war has forced more than five million persons to leave their homes and some four hundred thousand of them have arrived to Bogotá, the capital, and its surroundings in search of refuge. New Horizons houses the displaced for free, offering them guidance, company, and time in the difficult months after their arrival. During her first visit Meghan led an impromptu workshop where she invited residents to etch city scenes onto paper. The images of cars and buildings made that day populated the foundation’s scarce private spaces for weeks to come, inviting conversations about the novelty of life in the capital and its many promises. “My mom made a building,” Ricardo, who was nine at the time, told me of the etching of a purple rectangle hanging askew from the family’s dresser. “I want to live in one like that one day.” He had only lived in a wooden house aloft above the waters of the Pacific before arriving to the shelter and had never been in a building taller than five stories.

That first visit also sparked a conversation with Meghan about the connections between art making and ethnography that culminated with her return to Soacha seven months later. During her month-long visit, she stayed a few blocks from the foundation, coming over daily to paint its residents. In the course of two weeks she produced 12 portraits featuring 26 people and a dog. Sitters were painted individually and in groups. Families and friends posed for hours as their bunkmates stared, at first with ardent interest, but as the days wore on and more people had had their turn in front of the unstretched canvas, mostly to poke fun at the awkward poses and sore legs. Yet every night, as Meghan carefully arranged her day’s work against a wall to dry, the foundation’s residents would gather to judge and tease the models, marveling at the details that identified them and to speculate about what these portraits might reveal.

A few days after the portraits were finished they were shown in a gallery in Bogotá’s historic district. Most of the sitters attended the opening, mingling with potential buyers, local artists, and curious passersby. For all of the models, it was the first time going to an art event; most had never been to a museum.

If the opening was a novel experience for the foundation’s residents, for most of the other attendees it was the first time they explicitly engaged with a group of displaced persons not begging for food and change in the city’s streets.

For Alberto, a banker who had heard about the opening from a friend, the experience was eye-opening; “you usually think of the victims of the war as being over there, like far” he said while looking at a portrait featuring three community members Gabriel, José Luis and Fernando, in an almost pastoral scene. “Honestly you have this image that is sort of pathetic, like they are only needy. But here, they look different. They occupy a different space.” He later approached Elsa, an elderly woman whose portrait showing her sitting pensively on a plush chair, adorned with golden jewelry was much celebrated that evening. After complimenting her, they struck up a conversation about restaurants in the city. She had worked as a chef in many of the places Alberto visited for years.

When I caught up with her later, she was ecstatic: “It was a great surprise to me! I never expected in my life to be so admired and followed! I even got a boyfriend! I was very motivated because I never ever thought I would be in an exhibition. I would see all those old paintings in the restaurants where I worked and I never thought about them. But now I could be anywhere!” Elsa’s portrait indeed travelled widely: a collector in Switzerland bought the original, and a print now hangs in Princeton University. All of the other originals were shown last spring in a solo exhibition in New York that also featured the publication of a monograph about the project.

It is perhaps important to slow the narrative here and consider the layering of expectations of visibility that accompanied the complex weave of images produced and sustained by Meghan’s artwork. For many of those with whom I had lived for two years in Soacha, my project became legible again through the lens of the portraits and their movement in the world. Though most of my interlocutors understood that I wanted to write something about them, and that the book that might come out of it would be available to the public, the form such product might take was nebulous to them – as it was, and continues to be, for me. Many were eager to have their stories told elsewhere and were enthused by the prospect that in sharing them they could have an effect in the world. But it was through the portraits that such expectations ceased to be ethereal promises and took a more concrete form, particularly since half of the profits made in the sale of the paintings would be donated to the foundation. In Meghan’s art, then, they could see themselves and they were witnesses to the circulation of their representation. The portraits offered a material reminder that in the aftermath of their dispossession, when their place in the world had been vitally threatened, there were still spaces they occupied where care is possible.

What first drew me to Meghan’s portraiture was its potential to render time visually, and therefore, to aesthetically represent the shelter’s intervention and my ethnographic engagement.

Photography is commonly used to capture quotidian moments witnessed by ethnographers, offering a species of proof of the researcher’s presence. Photographs in these works serve as evidence that attest to a sort scientific certitude, often masking the creative act that produces them. Paintings, on the other hand, call attention to their own creation, highlighting the efforts of those who construct them. Meghan’s portrait-making process, as her insistence on live painting, is akin to that of ethnography in that it demands that artist and subject spend time together and it is through that shared time that the creative product takes its shape. Her style is particularly effective in this regard. Visible brushstrokes, a red under painting that peeps through here and there, the stretched faces of children too restless to stay still for hours, all attest to the duration of time spent producing these portraits. That Meghan hung out in the foundation, sharing meals, stories, and time with those who sat for her is evident not just in the care with which she rendered something of her sitter’s lives but in their own insistence that part of them lives on through the art. In this regard, the portraits would be best understood as an enactment of the kind of intervention offered by the foundation; offering a place of respite so that time as a shared experience can be remade.

In the end, the artistic project was a riposte to these concerns and much more. Megan’s paintings lit a fuse within the foundation, its residents, visitors, and friends, releasing an unexpected surge of energy and activity that we could have hardly anticipated. For Juan Carlos, for example, the paintings represented a physical proxy of his ethnographic experience. “I felt that a little bit of me was going away and that I was keeping a little of that faraway place” he recalled. “I felt recognized by Meghan and by you [Sebastián], that I was someone worth taking to. I wanted to be in New York! I also felt grateful that you took me with you, that you listened to my story and that you cared.” The idea of travel and circulation of a person as a story through a painting highlights the imagined trajectories of self-representations through ethnography.

Franklin and José, used starkly similar language to describe how they felt when they saw their portraits in the gallery in Bogotá: they felt big. Certainly their images were large, but they were also allowed to occupy a space that was previously denied to them. José, for example, recalls thinking that “at the beginning I thought that I wasn’t really anybody to be painted. But then I felt like I could be painted.” For a person whose life has been threatened, who has been removed from his home with his family without response or interest from the national government, a sense of having a place in the world may matter a great deal. To feel big might also mean to take space through an object that carries a validating trace of their presence.

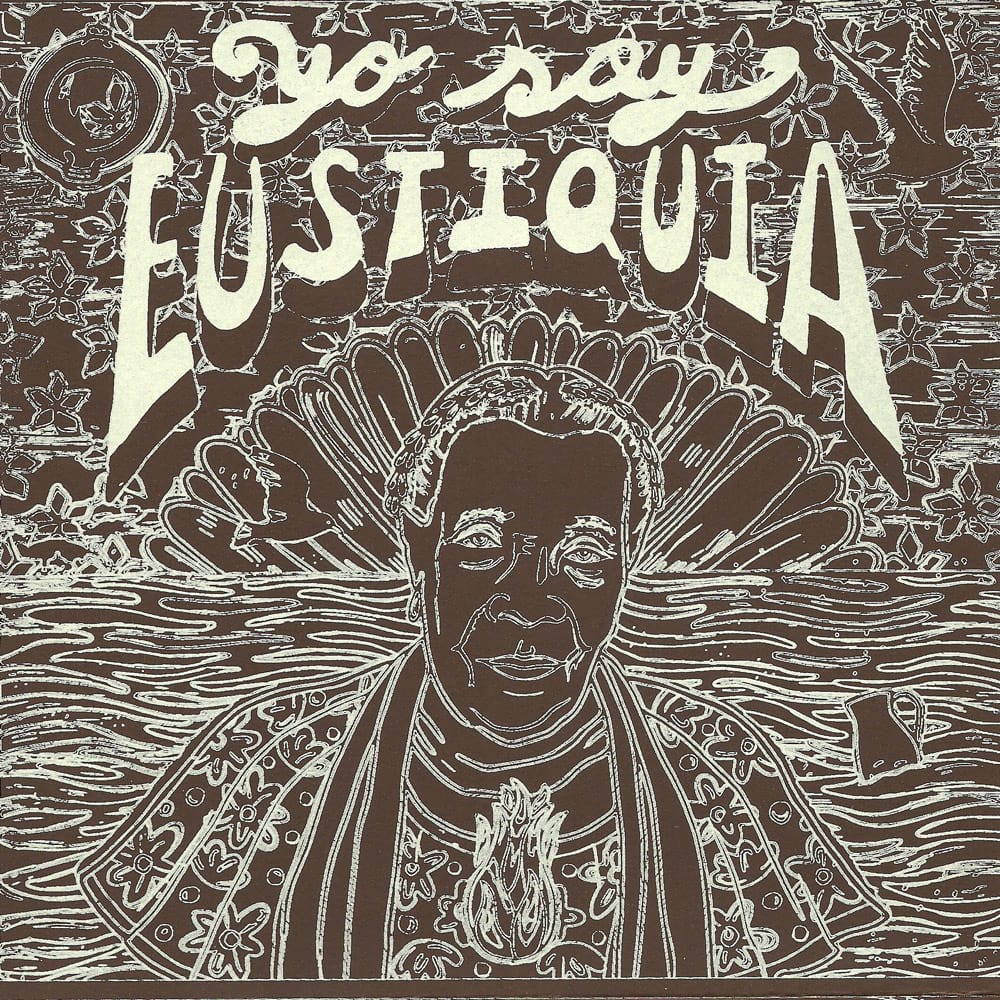

We may also recall Angie’s recollection of a hurtful racial slur while she sat for Meghan. Being an Afro-Colombian in the country’s interior is to be a body out of place. Under colonial rule, black populations were restricted to the coasts, especially the Pacific, and national segregation continued largely unabated well into the twentieth century. Massive displacement fractured the bonds of geography and race, casting black bodies both as danger and contagion in cities whose racist histories were allowed to go unremarked until the present day. For Angie and other Afro-Colombians, this meant a daily barrage of racial aggressions that ranged from the subtle dismissals at job interviews and government offices, to outright hostility by strangers in the street. Juan, hoped his portrait addressed this; “I thought when you take the image from Colombia, what would people outside think of us here, about us who are Afro-Colombian. Usually they take the worst part of the Afro-Colombians but never the best. So people go for the worst and don’t think about what we have, our race, our culture.” For them, the portraits’ international trajectory allowed them to escape the national bounds where their own movements were suspect, and instead enter directly into an imagined cosmopolitan arena where race could be configured differently.

The portraits also reverberated in more intimate quarters, making their presence and connection palpable to others far away. Maritza, Juan’s wife, gave her mother the photo of her portrait; “I can tell my mom that a woman came from the United States and it was nice. We were as a family. My mom put it up on the wall to remember me.” For Juan, who used to be a community leader before he received a death threat, the photo served as proof of how far he had traveled and what he had undergone throughout his displacement. “I had a photo of the picture and when we went back to [my home town of] Tumaco I would show it to people. The people usually didn’t think that it was us in the painting so I showed them a picture with Meghan.” If I found the genre of photography initially limiting in its easy conflation with objectivity and proof, it was exactly these aspects of it that called to Juan, casting his displacement as a leg in a continuous journey of growth and human experience. The painting as well as the photo documenting it provided concrete proof of his displacement and reframed the event as a form of ascendance rather than defeat.

João Biehl (2016) recently wrote on ethnography as an open system in which the circuits of fieldwork and time implicate anthropologists and their interlocutors in situations where lived lives and our representations of them are folded in upon one another. Aesthetic interventions are particularly apt mediums to explore such systems because they provide continuous opportunities to reflect back on and reinterpret the very practice and experience of ethnography. As can be gleaned from my particular experience of doing fieldwork alongside Meghan (a painter and print maker committed socially engaged art), ethnography via public art or other visual mediums possess the power to push public consumption a step beyond the traditional ethnographic publication (academic article or book). As anthropologists we often seek to overturn stereotypes and provide theoretical backing to a variety of human narratives and historical events. Weaving ethnographic accounts into visual documentation (particularly that which is produced by hand) and creative public programs both allows the content to be consumed by larger audiences and for the storytellers themselves to engage (literally and metaphorically) with this public.