Seasoning the American Dream: Stories from the Life and Times of Alicia

Written and Compiled by Alejandra Salamanca Osorio

The Taste of Politics

New York, is in many ways, a seductive city. Always capturing the world’s attention through photographs, and in movies with its grand buildings, extravagant skyline, big streets, and bustling citizenry. It is an imaginary city, presented to us who live on the outside, as a dream. A dream far from Colombia’s lack of infrastructure, poverty, and underdevelopment. That alternative landscape of fantasy, prosperity and modernity came to Latin America in the 1990s. ‘Third World Countries’ started to receive intervention to increase national GDP and for development. With the globalization of neoliberalism, privatization, and international trade agreements, Colombian President Gaviria started the Apertura – the Economic Opening. For us, it was clear, because new international business and the USA military arrived in Colombia. For them, we were broken, and we needed to be fixed by that foreign and paternalist assistance. Colombian cultural identity was devalued, and everyone wanted to be anything but Colombian.

Those times were tough for us. The incredibly exploitative drug trade, became connected to politics, corruption, and eventually human trafficking. Violence was a quotidian gesture. Our territories were sacrificed to make a few people rich. The truth is that the country is still ruled by corruption and narco-traffic, and that truth hurts. While this industry supplies the U.S. and Europe with a ‘lifestyle,’ popular discourse, news and media say that Colombians remain the problem. As such, we are the ones forced to feel shame, to be punished and ‘improved’ by developed nations.

But with all this pain and suffering came a new question: Why have our country fixed by the United States, when instead we could have direct access to that promised dreamland? Why not start a new life?

Seasoning the American Dream

Many Colombians migrated to the United States with an appetite for something different. For Alicia, the desire to migrate, came from human necessity. She needed to discover new forms of social mobility, and desired adventure, the opportunity to traverse new landscapes, and to travel across life itself. Alicia arrived alone to John F. Kennedy International Airport on a cold February evening in 1990. She did not know any English and was in her fifties. She was motivated by a desire for anonymity, for freedom. And what better place to come to one might ask, than New York City. Motivated by her own impulse to survive, Alicia wanted a new opportunity to help her family back in Colombia. Her goal was to provide them with a new reality, in a country where social mobility is almost non-existent. “For me, nothing was impossible. I never stopped because my youngest daughter and grandson depended on me. I didn’t have a pension, and I had already sold the car, as woman of my generation, there was nothing left for me in Colombia. Nothing. I had find a solution to the situation. That’s why I went to NYC to work, and that’s where the story began.”

Alicia spent her first month in NYC in Kew Gardens with a Colombian friend. At that time, she started to work in a house taking care of an older woman. For Alicia, the experience of migration was also an exploration of connections, kinship, favors, and networks; these connections also came to represent access to particular landscapes, opportunities and realities.

For me, nothing was impossible. I never stopped because my youngest daughter and grandson depended on me. I had to find a solution. I do not regret anything, with my effort, I travelled to a different city. I obtained my residence. I worked, and I became an American citizen. I achieved all that I wanted for my family and I. That’s why I went to NYC to work, and that’s where the story began.

The first New York that Alicia experienced was very different from her expectations. All the buildings and all the people looked the same. Her life turned into constant repetition. She became bored, and wanted more. After a few months, Alicia connected with another friend of the family. Then she opened the door to a different neighborhood, one full of migrants, diversity, and movement – Jackson Heights! “I thought it was fabulous, it was like a festival, like a little chapinero that Roosevelt.

Amazing! So, I stayed there, living, sharing, that was a novelty after that loneliness.” However, Alicia lost her previous job and needed to find a rapid solution to her unemployment. She wasn’t afraid. Alicia felt and still feels that luck is always on her side, that she is the owner of her destiny because she is full of faith.

Embracing the Challenges of Street Food Vending

Alicia randomly met another Colombian one day in the church. His name was Mr. Luis. He offered her employment as a street food vendor. Alicia accepted this new life of selling pinchos amid Jackson Heights.

“I started my job, and I was wearing my shorts and a very elegant blouse. I was feeling good, relaxed. Then the police arrived. They asked me about my permission to work there; they said I couldn’t work there during the day. I told Mr. Luis that the police took me out of there. He said, well… then let’s go to work at night.”

I thought it was fabulous, it was like a festival, like a little chapinero that Roosevelt Avenue. Amazing! So, I stayed there, living, sharing, that was a novelty after such loneliness.

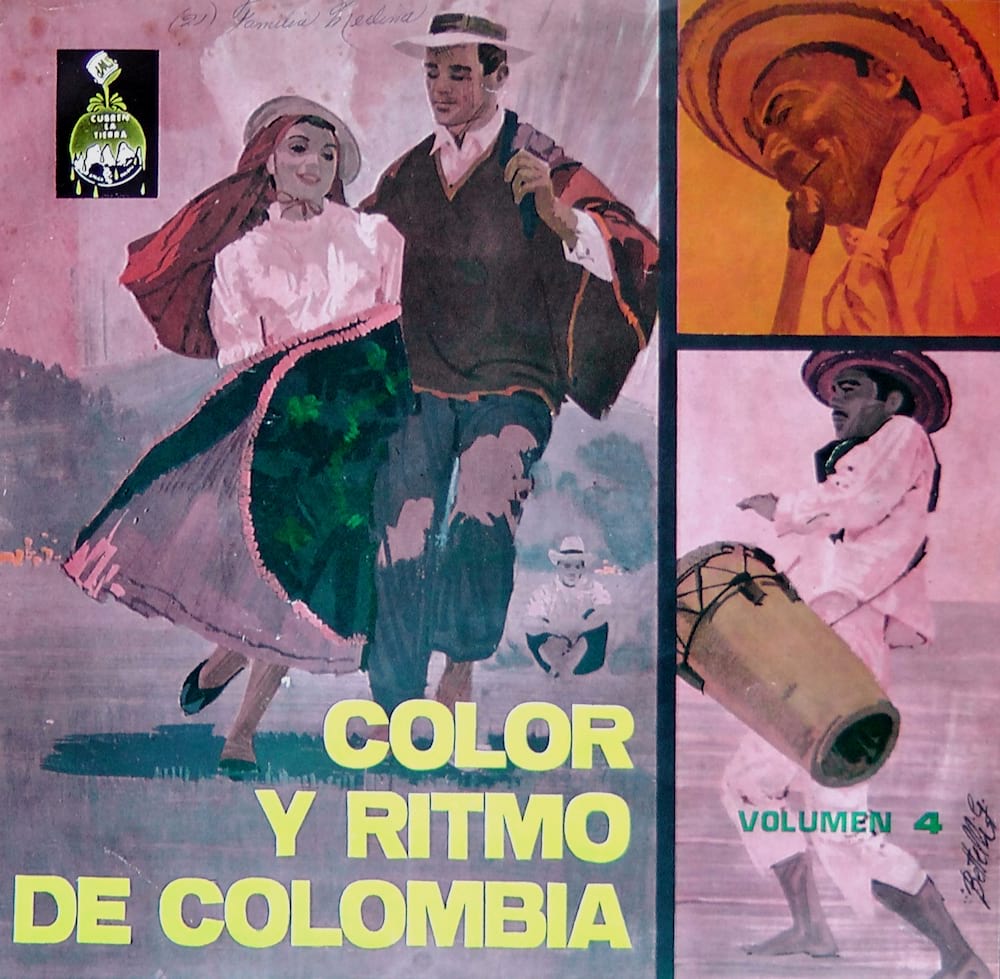

The tradition of eating pinchos emerged in Colombia as a version of street fast food. With the rapid urbanization of cities in the 1980s, and with the new offer of nocturnal activities such as concerts, football matches and nightclubs, open BBQs started to be part of busy streets. Pinchos quickly became popular because Colombian stomachs have a big appetite for meat, but mainly for meat cooked on a coal-fire. Smokiness in our kitchens is a symbol of reunion, enjoyment, festivities and family. Pinchos are primarily made from beef and pork, that is seasoned a few hours before being placed on the grill. The seasoning typically includes spring onion, garlic, oil, salt and pepper, and sometimes beer, cumin, thyme or oregano, depending on the taste of the chef. Pinchos are served with boiled potatoes and a touch of ají. In some cases, the plate may also include arepa or plantain.

Women generally sell pinchos, and other food products to generate new forms of income to support their families. It is crucial to notice that street food vending across the globe is a largely female activity, which in multiple cases reinforces the situations of gender inequality. In Alicia’s case, participation in the informal economy as an undocumented immigrant exposed her to new forms of vulnerability. “The police used to come and take things from people. Everything. But no, I was not scared. They told me to pick things up. I didn’t care, and I carried on”.

For Alicia, her vulnerability served as a space of resistance and creativity. In her case, the informality of her everyday work life was a counterpoint to the impossibility of bureaucracy that affects, classifies and oppresses immigrants on varying levels, depending on race, religion, ethnicity, and social class. Yet, the desire to survive is often stronger than fear of the state and its control. There are always ways to find autonomy. Alicia found agency in knowledge of traditional Colombian food. “I was there selling alone. I had good luck, and I always sold everything. I managed the business because Mr. Luis used to drink a lot. I was there all night from 8 pm till 5 in the morning on 76th and Roosevelt doing everything alone.”

After a few months, Alicia started to understand the process of street vending. At that time, Mr. Luis offered to sell her his food cart for $2,500 dollars. She accepted and started running her own business. “The cart was no more than one meter long. I used to put the grill and then the charcoal and then the pinchos. I added a vibrant seasoning; it was sold with a small arepa, sometimes with bread. People also added the sauces that they wanted. The smoky aroma called out to people, intoxicating their nostrils and attracting them to my cart.”

At 4:30 am, all that crowd used to go out from the clubs. They were dying to buy pinchos with arepas, also the aborrajados. They fought for my aborrajados! I also sold a lot because at that time there were more than 30 drug dealers. That was crazy! All those people selling drugs bought my pinchos, and then, those who came to buy drugs bought my pinchos too. Everyone sold a lot at that time.

In one night, Alicia used to sell around two hundred pinchos for the price of 2 dollars each. Back in Colombia, her daughter and grandson, Andrés started to witness her success first hand. “She sent us our first VHS, TV with a remote control, and clothes by famous American brands,” notes Andres. “She didn’t send us letters. But sending those things was her form of showing us love, showing us that she was doing well in New York.” Keeping up with family ties across national borders manifested itself in the form of calls, and gifts. Things that Alicia perceived as valuable symbols of American success.

The years passed and working at night as a street food vendor became Alicia’s routine. 76th street was transformed into an intimate place. The heavily saturated social atmosphere and soundscape of popular latino club music, accompanied Alicia while she, amongst the smoke of her stove, sold Colombian delicacies. To her favor, she was situated right outside several iconic nightclubs of the era such as El Chibcha, and Añoranzas. “At 4:30 am, all that crowd used to go out from the clubs. They were dying to buy pinchos with arepas, also the aborrajados. They fought for my aborrajados!” The drug industry also emerged alongside Alicia’s success in Jackson Heights. “I also sold a lot because at that time there were more than 30 drug dealers. That was crazy! All those people selling drugs bought my pinchos, and then, those who came to buy drugs bought my pinchos too. Everyone sold a lot at that time.”

The cart was no more than one meter long. I used to put the grill and then the charcoal and then the pinchos. I added a vibrant seasoning; it was sold with a small arepa, sometimes with bread. People also added the sauces that they wanted. The smoky aroma called out to people, intoxicating their nostrils and attracting them to my cart.

Alicia worked hard. She used to go back to her house around 5:00 am and then at 11:00am she was off to buy meat and different ingredients in Astoria (the neighboring municipality). She prepared the pinchos, aborrajados and arepas in her house in the afternoon and then at 8:00pm she was on 76th, ready to sell again. At that time Alicia faced violence, illegality and marginality, something that she didn’t expect to experience when she moved to New York, because, in the Colombian imaginary, the United States is a place of freedom, equality and happiness.

“They always asked me to save them the money, to hide the drugs, they were coming next to me playing dumb. But no, I was clear, I didn’t want to have problems with the police, I was always saying leave me alone.”

Although working on the street was dangerous, Alicia persisted because she wanted to bring her daughter and grandson to live with her.

Delicious Visions

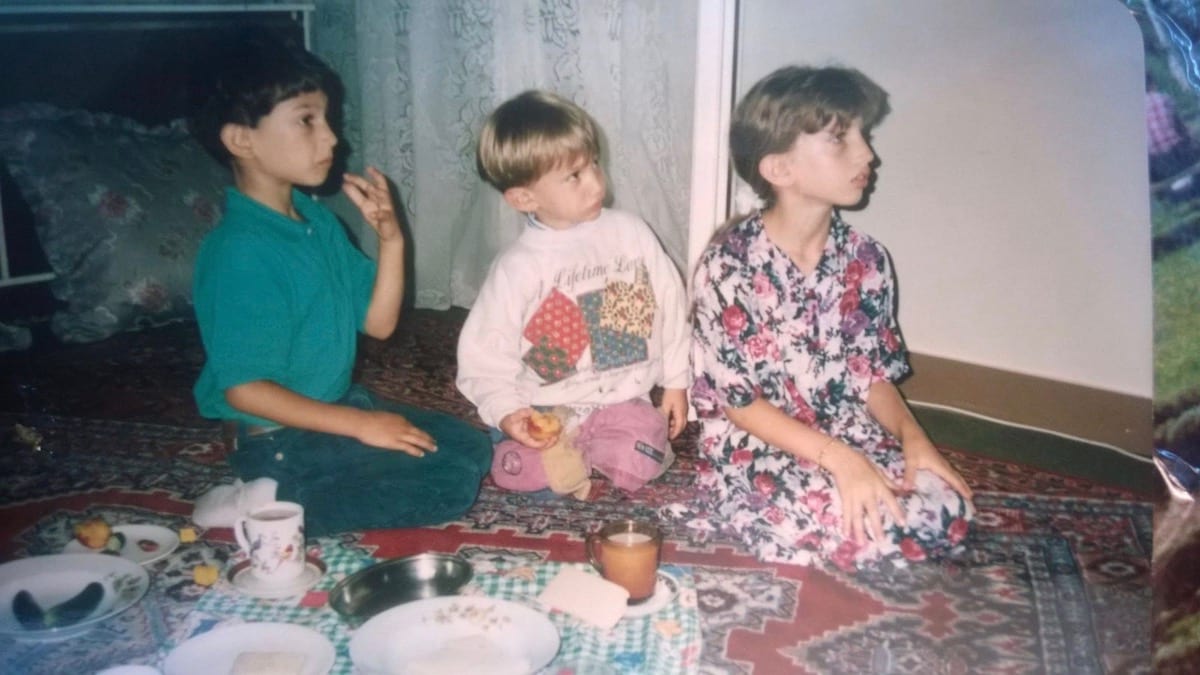

After seven years of hard work, Alicia’s family joined her in New York.

Alicia’s grandson, Andres, now works as DJ and culture worker in the city, which was once so difficult for his grandmother to traverse. The NYC that Andres lives in is a changed city. One where immigrant culture in now seen as a commodity and source of capital. He is an inheritor of Alicia, full of admiration for his grandmother, for her tenacity, strength and achievements, which provided him and his mother with a better future.

Looking back Andres notes, “I spent my first week in New York without going out of Jackson Heights. It didn’t look like the New York I was expecting, because I wanted to see all those tall buildings. But I realized that New York was more interesting than in those movies, full of different people, languages, cultures, there in just one city.”

Alicia, now living in Bogotá, remembers her time working in the United States. “I do not regret anything, with my effort, I travelled to a different city. I obtained my residence. Everything was fine. I worked, and I became an American citizen. I achieved all that I wanted for my family and I.”

Written by: Alejandra Salamanca Osorio

Audio & Illustrations by: Andres Aceves

© Los Herederos Inc. – All Rights Reserved

Seasoning the American Dream was produced by Alejandra Salamanca Osorio, an MA candidate at SOAS – School of Oriental and African Studies – University of London, as part of her Spring/Summer 2020 internship with Los Herederos. The internship program focused on developing digital models & methodologies for the investigation and sharing of traditional foodways in global urban spaces.